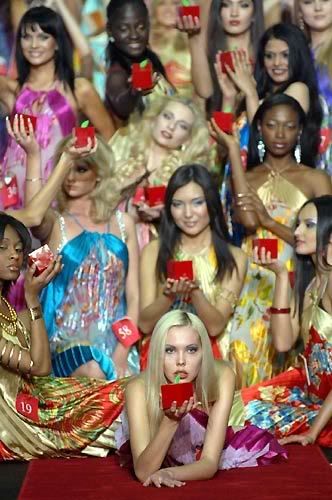

girl Kyrgyz are so beautiful and pretty! This site provides free girl Kyrgyz Photos, Hot girl Kyrgyz, girl Kyrgyz Videos, girl Kyrgyz Video Clips, girl Kyrgyz Dance, girl Kyrgyz Dancing, girl Kyrgyz, girl Kyrgyz Pictures, girl Kyrgyz Wallpapers, girl Kyrgyz Pics, girl Kyrgyz Images, girl Kyrgyz TV, girl Kyrgyz Models, girl Kyrgyz Celebrities, girl Kyrgyz Dating, girl Kyrgyz Singles, girl Kyrgyz Romance and many more.

Mountain Madness

When people who don’t know me too well hear that I am moving to Kyrgyzstan as a Peace Corps Volunteer, they often say, “Just think what you are giving up…” or “Just think what you are leaving behind.”

What am I giving up? What am I leaving behind? I’ve been thinking a lot about this and I suppose my attempt to put it to words is also an attempt to confront a reality I am about to face. That said, I don’t like the phrase, “just think what you’re giving up” or, “what you’re leaving behind?” I don’t like these phrases because of the negativity they connote. Giving up! Leaving behind! I’m not giving up and I’m not leaving behind. I am moving onward and bringing with me, not only the memories of a life lived elsewhere, but, the experiences, knowledge, love and morals that have made me who I am.

I am not abandoning those I love nor am I escaping from a life I don’t enjoy. I am blessed—I’ll be the first to admit that. I am not a religious man, but I’ve found no other term (lucky, serendipitous, fortunate) that embodies the blessed life I’ve lived. I have three wonderful parents whose unconditional support and love for me has never wavered. I have grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins—who, despite my spotty record of correspondence, love and care for me—as I do them. I have friends whose trustworthiness, devotion, self-awareness, intelligence, humility, imagination, wit, patience and forgiveness—challenge me, daily, to become a better human being. I have surrogate mothers and fathers who’ve taken me in, shared their food, their families and their friendship. These surrogate families have allowed me to become an extra sibling or son, break bread at their table and drink beer from their fridge. To all of you who read this: Please know, I have not taken your generosity and love for granted. Please know, You All shaped me into who I am. Please know, whatever good you see in me is simply a reflection of that which I learned from all of you. And finally, Please know how grateful I am.

So, I am not “giving up” and I am not “leaving behind”—then what am I doing? Why, after three years of law school and mountains of debt, am I volunteering for the Peace Corps in Kyrgyzstan? This is a good question. Part of my answer to this question can be attributed to my parents. From an early age, my parents instilled in me the importance of civic contribution. Through both words and deeds, they repeated the theme of “Giving Back”. My father “gave back” through his work as both a counselor and then administrator at a Pennsylvania state-run rehabilitation center and as an officer in the United States Army. My stepmother “gave back” through her work as both a social-worker, an occupational therapist, and as volunteer with various non-profit organizations and support groups. And, my mother “gave back” through her work in helping to bring safe pharmaceuticals to the market, as an organizer and peaceful protestor, and as an active and concerned member of her Unitarian/Universalist Church. Although they never said, “Son, look how much I’ve given back to society”, it didn’t take me long to realize how much their contributions meant to others. When you repeatedly hear from strangers how hardworking, smart, witty, caring and helpful your parents are, you can not help but be awe-inspired and prideful of your origin.

Throughout my life, my parents stressed the importance and value of contributing good to society. Although they never defined it for me, I define the giving of good to society as any action taken with the intent and purpose of achieving an end that places people or their environment in a better position than before the action was taken. This contribution, need not be purely self-less. Anyone who has volunteered their time, services or skills to assist another human being make a better life for themselves, knows the feel-good value of emotional cash that is redeemed when such a transaction takes place.

While some may argue that an action undertaken with the hope of redeeming such a reward is ultimately selfish, the fact that such action entails an intent and purpose that is “good”, preserves the value of that which was contributed. Simply put, helping others because it makes you feel good, does not reduce the value of any good you bestowed. In fact, I would argue that one of the most important parts of “giving back” is what you “take away”.

In the dog-eat-dog world of getting ahead, it appears to me that many have forgotten what one can “take away” from the experience of helping others. I know this is something I need to be reminded of and that is one of my reasons for volunteering in Kyrgyzstan. Other reasons will follow...

What am I giving up? What am I leaving behind? I’ve been thinking a lot about this and I suppose my attempt to put it to words is also an attempt to confront a reality I am about to face. That said, I don’t like the phrase, “just think what you’re giving up” or, “what you’re leaving behind?” I don’t like these phrases because of the negativity they connote. Giving up! Leaving behind! I’m not giving up and I’m not leaving behind. I am moving onward and bringing with me, not only the memories of a life lived elsewhere, but, the experiences, knowledge, love and morals that have made me who I am.

I am not abandoning those I love nor am I escaping from a life I don’t enjoy. I am blessed—I’ll be the first to admit that. I am not a religious man, but I’ve found no other term (lucky, serendipitous, fortunate) that embodies the blessed life I’ve lived. I have three wonderful parents whose unconditional support and love for me has never wavered. I have grandparents, aunts, uncles, and cousins—who, despite my spotty record of correspondence, love and care for me—as I do them. I have friends whose trustworthiness, devotion, self-awareness, intelligence, humility, imagination, wit, patience and forgiveness—challenge me, daily, to become a better human being. I have surrogate mothers and fathers who’ve taken me in, shared their food, their families and their friendship. These surrogate families have allowed me to become an extra sibling or son, break bread at their table and drink beer from their fridge. To all of you who read this: Please know, I have not taken your generosity and love for granted. Please know, You All shaped me into who I am. Please know, whatever good you see in me is simply a reflection of that which I learned from all of you. And finally, Please know how grateful I am.

So, I am not “giving up” and I am not “leaving behind”—then what am I doing? Why, after three years of law school and mountains of debt, am I volunteering for the Peace Corps in Kyrgyzstan? This is a good question. Part of my answer to this question can be attributed to my parents. From an early age, my parents instilled in me the importance of civic contribution. Through both words and deeds, they repeated the theme of “Giving Back”. My father “gave back” through his work as both a counselor and then administrator at a Pennsylvania state-run rehabilitation center and as an officer in the United States Army. My stepmother “gave back” through her work as both a social-worker, an occupational therapist, and as volunteer with various non-profit organizations and support groups. And, my mother “gave back” through her work in helping to bring safe pharmaceuticals to the market, as an organizer and peaceful protestor, and as an active and concerned member of her Unitarian/Universalist Church. Although they never said, “Son, look how much I’ve given back to society”, it didn’t take me long to realize how much their contributions meant to others. When you repeatedly hear from strangers how hardworking, smart, witty, caring and helpful your parents are, you can not help but be awe-inspired and prideful of your origin.

Throughout my life, my parents stressed the importance and value of contributing good to society. Although they never defined it for me, I define the giving of good to society as any action taken with the intent and purpose of achieving an end that places people or their environment in a better position than before the action was taken. This contribution, need not be purely self-less. Anyone who has volunteered their time, services or skills to assist another human being make a better life for themselves, knows the feel-good value of emotional cash that is redeemed when such a transaction takes place.

While some may argue that an action undertaken with the hope of redeeming such a reward is ultimately selfish, the fact that such action entails an intent and purpose that is “good”, preserves the value of that which was contributed. Simply put, helping others because it makes you feel good, does not reduce the value of any good you bestowed. In fact, I would argue that one of the most important parts of “giving back” is what you “take away”.

In the dog-eat-dog world of getting ahead, it appears to me that many have forgotten what one can “take away” from the experience of helping others. I know this is something I need to be reminded of and that is one of my reasons for volunteering in Kyrgyzstan. Other reasons will follow...

Posted by

Elinda Tarra Lie

Ewa's

Snowstorms and airports, hotels and taxis. Last week I was stranded in the capital of Kyrgyzstan, living a Sisyphean life between shuttling to the airport in the morning and returning, dejected, to the hotel in the evening. Osh received a gracious 4 feet of snow in a three day period of time--hence the no-flight scenario.

Back in Osh and the weather has been a balmy 55 degrees the last three days. All the snow has nearly disappeared and sinkholes are emerging all over the city. A married volunteer couple here in Osh (Glen and Linda--who I've come to calling "Glenda") had a sink hole emerge smack dab in the middle of their host-family's property. They say they can hear the rats scurrying around in the space the hole has created beneath the foundation of the building and the floorboards. Nothing like the pleasant sound of pestilent rodents to help you sleep.

I'll be writing more soon. Hope all is well.

Larry

Posted by

Elinda Tarra Lie

Often in Life, the Reverse is True.

The Shock…oddly not so shocking. Perhaps I overbuilt, over-anticipated and over-analyzed it. Perhaps, since I’ve done this before, the waves from previous shocks canceled themselves out. Or, maybe, I’ve simply grown callus and thick-skinned. At any rate, the event of not experiencing what travelers have tritely termed “Reverse Culture Shock” has, in fact, left me shocked.

Perplexed might be better word for it. Returning to the U.S. from previous sojourns in foreign lands, resulted in shock and awe. I remember arriving home from six months in S.E. Asia and laying on the couch for days, my mouth agape, a pool of spittle darkly expanding into the pillow’s blue fabric as my drying retinas captured thousands of images on CNN.

After another six month trip in Indonesia, I remember looking into the eyes of average Americans and thinking there are whole other worlds and harsher realities that you are free to ignore. And I remember, simultaneously pitying and admiring those who preferred the safety of the shadows in Plato’s cave, over exploring what’s beyond the walls of their coddled world. Sounds harsh and arrogant, I know. But remember, I was in college; young, idealistic and empowered by a new vision of the world, so I don’t think this view was as arrogant as it was selfishly naïve—I had simply wanted everyone to understand and see the world with the same eyes I had.

That was in 1996 and I remember the guilt I experienced for having left behind those on the island of Sumatra who had shared their lives, their food and their friendship with me. The Indonesian people I’d met had shown me that the world was indeed harsher than any reality I’d known back home. Yet, they’d also taught me that their struggle to survive could bring entire communities together in beneficent ways I’d never experienced before. How could I forget them so easily—I wondered one day, while sipping cappuccino and journaling in my laptop at my cozy local café.

And now I journal again—this time from Kyrgyzstan. And I am shocked—shocked at how easy it was to return to my life back home in the U.S. I wasn’t surprised by the oft caricaturized gluttonous consumerism we Americans partake in. I wasn’t amazed at the unreflective ease with which we whisk away our waste: our trash disappears by truck and our turds go down the toilet—easy as apple pie. I wasn’t stunned by the apathy we Americans display towards our government: the gross deficit spending; the federal indictments of politicians on corruption and obstruction of justice charges; or, the executive branch’s impingement on the same Freedoms that we ironically hold up as beacons for other “emerging democracies” to follow.

Reverse Culture Shock? Nope. This time when I returned to America, it was pretty much how I expected it to be. Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to sound cynical. I love the United States. I love the opportunities and freedoms it affords me. I love serving my country as a Peace Corps Volunteer. I love my friends, my family, my latte from my little corner café. I love that I don’t have to bribe the mailman to get my mail. I love that I can drink water from the tap. I love that I rarely see used hypodermic needles on the street and that there is little bent rebar for children to impale themselves on. I love that the manholes are covered. These are all really good things about the U.S. that I love and all I’m trying to say is, I wasn’t shocked by the culture when I returned after being away for over 15 months.

Reverse Culture Shock? Nope. This time when I returned to America, it was pretty much how I expected it to be. Now, don’t get me wrong, I’m not trying to sound cynical. I love the United States. I love the opportunities and freedoms it affords me. I love serving my country as a Peace Corps Volunteer. I love my friends, my family, my latte from my little corner café. I love that I don’t have to bribe the mailman to get my mail. I love that I can drink water from the tap. I love that I rarely see used hypodermic needles on the street and that there is little bent rebar for children to impale themselves on. I love that the manholes are covered. These are all really good things about the U.S. that I love and all I’m trying to say is, I wasn’t shocked by the culture when I returned after being away for over 15 months.Of course, there were the little differences that I will tell my fellow Peace Corps Volunteers about. The choices for diet, low-fat, low-cal, low-cholesterol, low-carb foods seem to have expanded by an exponent of 10.

And then there’s those little blue tooth microphones parasitically attached to an ear of every male between the age of 25 and 40. Wandering through the shoe section of a department store, I thought yuppie schizophrenia was plaguing our nation, “Honey,” one well-groomed man said endearingly as he looked under the tongue of a Nike sneaker for what I could only assume was his imaginary wife. I stared at him for a moment wanting to say, “Trust me pal, if you think your wife’s in there then you’ve got bigger problems than figuring out which pair of running shoes to buy.” He set the Nike down, picked up an Adidas and went on talking, “remember the Shelton’s girl doesn’t eat meat…uh ha…yeah, or maybe we could just order her a pizza.” It wasn’t until he caught my gaze and cocked his head that I realized this was some sort of new communications device employed to induce recently returned Peace Corps Volunteers into feeling ashamed for even thinking that a man who talks to Tennis shoes might be a few California rolls shy of a sushi platter.

But overall, things haven’t changed that much. And in some ways, I am thankful for the stasis. My friends and family are still the intelligent, caring, friendly folks they’ve always been. My girlfriend still amazes me with her emotional empathy, intellectual curiosity and overall excitement towards life. And the beer, oh the beer…it’s as bubbly and belch inducing as ever.

I met a few new people on my visit home; Solena’s parents and her good friends being among the most important—oh, but don’t let me forget the new babies too, Skylar, Will, Max and a few of my old favorites Loren and Fisher.

I got to see Penn State win the Orange bowl in triple over-time and Texas upset USC. The Pittsburgh Steelers walloped Cincinnati and I watched Kevin Garnett (live at the Target Center) dunk on the Mavericks.

In short, things seemed to be in order back home. I’m now back in Kyrgyzstan (AKA Home #2) and things here seem pretty much the same too. Four beautiful, equalizing inches of snow have blanketed Osh. Trash has disappeared beneath the pristine glitter of white crystals and everyone seems more alive, more dimensional on top of that snow—it feels like we are all sketches come to life, dancing atop the same white page we were once penciled onto.

As for the rest of the news back here Kyrgyzstan, well, it looks like I will be on an extended vacation from the Center for American Studies. Osh State University’s campus is closed (meaning no heat) until February 1st. So, I’ve been asked to hold tight till then. Don’t worry, I know how to keep myself busy. We are working on a grant for dictionaries, TOEFL materials and (a long shot) an LCD projector. Grant deadline: 11 days.

Well, that’s all I got folks.

Posted by

Elinda Tarra Lie

Come with me

“Come with me.” He said and put his arm around my shoulder. We walked outside onto the porch and into the fresh air, then down the stairs and into the flower garden. In the distance I saw a group of children playing soccer and others completing their yard work. The grounds of the orphanage included stables, a few acres of farmland, a pig pen and dozens of caged bunnies.

“You see,” he said, “I used to get drunk every night and chase women. I lived most of my life like that. One day I asked myself, Stephan, what have you done with your life—what do you have to show for yourself?—and the answer was nothing.”

He leaned over and stuck his nose in the white blossoms of a rose and inhaled.

He raised his head and we continued strolling, “At that point in my life I already had a fairly successful business, but I realized that didn’t matter. I looked around and saw all of these children on the streets, abandoned and begging. And I said, there’s something I can do.”

Several of the children spotted Stephan outside and began shouting, “Pappa! Pappa!” A little, sandy-haired girl with wide eyes glowing above her smile sprinted into Stephan’s arms. He lifted her up and looked at me, “now I have twenty-one children that all call me pappa and everything I do, I do for them.”

I took another look around the orphanage and felt as though I was in the center of big family. Stephan knelt and set the little girl back down and looked up into my eyes, “Life should be about love.

Posted by

Elinda Tarra Lie

Reasons for Joining the Peace Corps

Reasons for Joining the Peace Corps: Part II

This is the second part of a series of entries articulating (as best I can) the reasons why I joined the Peace Corps. (click on the link above to see the first entry: Questions and Answers Re: My Departure)

Another reason I chose to join the PC was to fulfill my desire to live and work in a country that is totally foreign to me. After traveling through S.E. Asia and living in Thailand for four months in 1994 and in Indonesia for 6 months in 1996, I knew that a portion of my adult life would be spent overseas.

Traveling, for me, was the shaking of the proverbial champagne bottle before the ceremonial uncorking. Never before had so many questions, self-reflections, and personal discoveries effervesced into self-awareness. Before I took off for Asia, my life had distilled, settled and sat on a shelf (my parents, who exposed me to endless cultural events from museums and folk festivals to political rallies and military ceremonies, would undoubtedly argue with my assessment of having lead a settled life). When I applied to Saint Olaf College’s Term in Asia program in 1994, it was like watching from the shelf, knowing you’re about to be the next bottle to make it out of the store.

After monkeys and Buddhists, pagodas and yaks, elephants and spicy-toosh, motorcycles and Great Walls, Terra-Cotta warriors, bamboo and sticky-rice, chuk-chuks and tuk-tuks, and Forbidden Cities and crocodiles, my life was shakin-up and uncorked.

As with any uncorked bottle of champagne that’s been shakin-up, you better dump it all over the person standing next to you or drink it down fast. I chose to drink it down fast. I wish I could share how intoxicating some of those first moments were: Standing atop the roof of the Yale guesthouse at the Chinese University of Hong Kong on my 20th Birthday, drinking Carlsberg beer and discussing inter-religious dialogue with my religion professor; teaching English to young Thai girls who were at risk of being sold into prostitution; painfully trying to meditate at a Buddhist monastery; watching a 90 year-old Thai woman roll perfect banana leaf cigars; dodging fireworks while watching the evanescing glow from thousands of lanterns as they floated slowly down the Mekong river; being attacked by a thirsty orangutan who stole my bottled water. Those moments, once trapped in a bottle, were worthy of uncorking the finest bottle of champagne.

When world-travelers sit-down and share their experiences with one another, I’ve found there's a thread of commonality between them. Part of that common thread is a feeling of self-reflective “aliveness” that manifests during extreme experiences. When overseas, simple, everyday acts present challenges which our analytical western minds try vigorously to comprehend: Squatting over a toilet turns into a discussion of why many cultures don’t eat or shake with their left hands; witnessing bamboo scaffolding surround a skyscraper turns into a metaphor for East meets West; watching a man sweep dust off the sidewalk but avoid removing plastic wrappers and water bottles turns into a debate over the Eastern perspective of what garbage is. In strange lands, every profane experience ripens into potential for the profound.

For me, reflecting on these simple everyday events elicited a more intimate inquiry into my own sense of life, self and being. Who am I? What is the purpose of my life? Am I a “good” person? What is the value of being “good?” How can I become better a human being? What would “I” like to become? These existential questions are painfully banal, but the fact that they are commonplace does not diminish the value inherent in how one arrives at them. For me, these questions were conjured simply by participating, observing, and reflecting on everyday life in a foreign land.

For example, imagine you’re invited to a funeral by the Batak people of Sumatra, Indonesia—you arrive wearing your mourning face (even though you have no idea who that dead person is laying on the ground in front of you), but you quickly realize very few people look sad. In fact, a lot of the women are dancing and singing while their men stand off to the side smoking cloves and sipping Tuak (a sour palm wine). Next thing you know everyone’s stuffing their face with the water-buffalo, which, just moments ago, was alive and nibbling on that Batik shirt you’re wearing “to blend in”. Aren’t funerals supposed to be sad? As soon as you ask that question, you look over and see three women wailing uncontrollably over the dead man’s body. What’s going on here? You start asking more questions, “Who was this man? Why are there so many people here laughing? Who were those sobbing women? Why is this water-buffalo meat so stringy? What does it mean to die in Batak land? Do they believe in an afterlife? Did somebody just say “cannibalism”?

And then your mind starts trying to make sense of it all. Usually, it begins by finding something familiar in the foreign. “O.K, those women were crying, so obviously some folks here are sad.” You note too, that people have gathered together and dressed up for the occasion—that’s similar…Phew!—you wipe your forehead with the back of your hand and scan the scene for more similarities. After awhile, you’ve grabbed enough pieces to start assembling a new world that’s a little easier to understand.

Fast-forward three months…the pieces of this damn puzzle won’t fit together!...Every time you think you’ve got it figured out, a new piece arrives: Witch doctor’s; snake whiskey; crocodile meat; corruption; houses built to resemble boats; drinking pig’s blood; political rallies; sinking ferries; rubber-plantations protected by scowling men with AK-47s, etcetera. With every new piece, you are forced take apart a world you thought you had just figured out.

Some of the greatest moments of my life have been lived during this process of deconstructing and reconstructing worlds. The energy it requires is immense, however, the reward—paid in the currency of self-knowledge—is even bigger. And that’s the irony too—you spend all this time and energy trying to figure out another culture, and you wind up learning so much more about yourself in the process. This is another reason why I chose to join the Peace Corps. (more to follow)

Posted by

Elinda Tarra Lie

Expectations are planted

After accepting your Peace Corps Assignment, Peace Corps requires Invitees to complete an aspiration statement and Resume to be viewed by the in-country staff. The Format for the Aspiration Statement is as follows:

Expectations

Strategies for adapting to a new culture

Personal and professional goals

(please note: PC prefers responses limited to one typed page)

The Following Aspiration Statement will be submitted tomorrow, June 26, 2004:

Expectations are planted, like seeds, deep into the furrows of every volunteer’s mind. Come harvest time, the expectations I have sown should be flexible enough to bend easily with the changing winds of community needs. I expect my Peace Corp service to be almost nothing like I pictured it. I expect to be challenged by language and Kyrgyzstani culture and mildly frustrated with the remnants of soviet bureaucracy. I expect pre-service training to provide me with a foundation of the policies, skills and resources that are necessary to equip a creative, patient, practical volunteer for two years of SEOD service. I expect to learn much about the operation, structure, and implementation of NGOs. Finally, I expect my PC service will yield more rewards than I ever could have imagined.

Strategies for adapting to a new culture are often subjective and dependent on the world-view of the individual adapting. For me, strategy begins at home: absorbing cultural information; familiarizing myself with the Cyrillic alphabet and basic Russian and Kyrgyz languages; reading PCV blogs, NGO development manuals and RPCV books (such as, This Is Not Civilization (2004) and The Great Adventure (1997)). Having studied two semesters abroad in Thailand (8/94-2/95) and Indonesia (12/95-6/96), I understand that almost nothing is what you expect it to be. Flexibility, patience, creativity, and a sense of humor are often called upon to endure those times when Reality and Expectations don’t quite meet eye-to-eye.

When thirty-years of flesh plop down in a foreign country, adaptation becomes a bridge between the old self and the amorphous, future You. In order to cross this bridge without falling, I plan on holding on to two fundamentals that run like handrails across the cultural divide. First, I will hold onto my desire to learn the language(s) as best I can. And second, I plan on remaining patient and refraining from fast judgments based on incomplete knowledge of a culture I am trying to understand. By holding onto these fundamentals, I hope to look back and see that I have crossed into a Kyrgyzstan that is a little less foreign than when my journey began.

Personal and professional goals can not be over-stated. My becoming a PCV was not spawned from a directionless decision to do something with my life after college. I am not wet behind the ears and dripping with naiveté. I am a licensed attorney, who is consumed more by a desire to contribute to the good of the world than the consumption of worldly-goods. I chose Peace Corps and happily Peace Corps chose me. That said, my personal goals remain quite simple: maintain patience and flexibility, learn the language and history of the Kyrgyz peoples, participate in cultural events and complete my service. Professionally, I hope my Peace Corps experience will assist me in further developing a skill-set that may be utilized throughout the remainder of my life. Whether I continue down an international path of NGO development work, pursue a career with the Foreign Service or choose to return to the practice of law, my goal as a PCV is to acquire the knowledge and experience necessary to assist regardless of where my life takes me.

Posted by

Elinda Tarra Lie

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)